As with the droppings of the Questing Beast, we recognise synchronisation code paths by their emissions. But even when not leaving telltale fewmets, these creatures wander among us unseen, unsung, until shutdown doth us part.

The place of the SOS_UnfairMutexPair

Bob Dorr has done a great job of illustrating why thread-safe SQLOS memory objects need serialised access in How It Works: CMemThread and Debugging Them. This has been followed up by the “It just runs faster” coverage of dynamic memory partitioning.

Today I’ll be examining the SOS_UnfairMutexPair, the synchronisation object behind memory allocations. While I’m going to describe synchronisation as a standalone subject, it’s useful to think of it as the CMEMTHREAD wait; to the best of my knowledge nothing other than memory allocations currently uses this class.

For context, I have previously described a bunch of other synchronisation classes:

- The EventInternal, which underpins all cooperative waiting. Note that this has been reborn as WaitableBase in SQL Server 2017.

- The SOS_Mutex.

- The pre-2016 SOS_RWLock.

- The 2016 reboot of the SOS_RWLock.

- The SOS_WaitableAddress.

- Latches, which may not be part of SQLOS, but have influenced SQLOS synchronisation. The Latch Files: Out for the count is a good intro to the rich use of atomic compare-and-set operations we’ll see in simplified form today.

- And who can forget those busy beavers, the spinlocks, both the ones who leave droppings and the ones who don’t?

One picture which emerges from all these synchronisation flavours is that a developer can choose between busy waiting (eagerly burning CPU), politely going to sleep (thread rescheduling), or a blend between the two. As we’ll see the SOS_UnfairMutexPair goes for a peculiar combination, which was clearly tuned to work with the grain of SQLOS scheduling.

The shape of the object

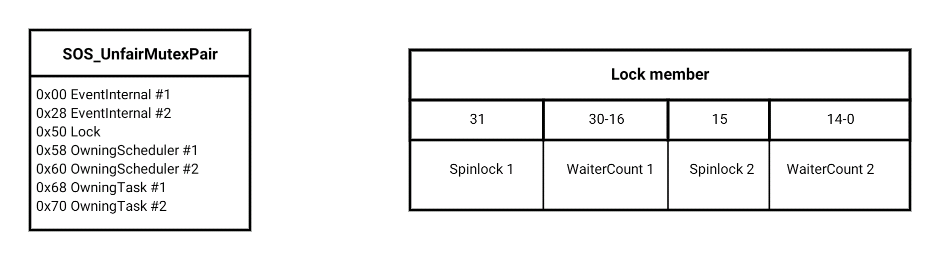

With the exception of the central atomic lock member, everything comes in pairs here. The class models a pair of waitable objects, each having an associated pair of members to note which scheduler and task currently owns it:

Although it exposes semantics to acquire either both mutexes or just the second, in its memory allocation guise we always grab the pair, and it effectively acts as a single mutex. I’ll therefore restrict my description by only describing half of the pair.

Acquisition: broad outline

The focal point of the mutex’s state – in fact one might say the mutex itself – is the single Spinlock bit within the 32-bit lock member. Anybody who finds it zero, and manages to set it to one atomically, becomes the owner.

Additionally, if you express an interest in acquiring the lock, you need to increment the WaiterCount, whether or not you managed to achieve ownership at the first try. Finally, to release the lock, atomically set the spinlock to zero and decrement the WaiterCount; if the resultant WaiterCount is nonzero, wake up all waiters.

Now one hallmark of a light-footed synchronisation object is that it is very cheap to acquire in the non-contended case, and this class checks that box. If not owned, taking ownership (the method SOS_UnfairMutexPair::AcquirePair()) requires just a handful of instructions, and no looping. The synchronisation doesn’t get in the way until it is needed.

However, if the lock is currently owned, we enter a more complicated world within the SOS_UnfairMutexPair::LongWait() method. This broadly gives us a four-step loop:

- If the lock isn’t taken at this moment we re-check it, grab it, simultaneously increment WaiterCount, then exit triumphantly, holding aloft the prize.

- Fall back on only incrementing WaiterCount for now, if this is the first time around the loop and the increment has therefore not been done yet.

- Now wait on the EventInternal, i.e. yield the thread to the scheduler.

- Upon being woken up by the outgoing owner releasing the lock as described above, try again to acquire the lock. Repeat the whole loop.

The unfairness derives from the fact that there is no “first come, first served” rule, in other words the wait list isn’t a queue. This is not a very British class at all, but as we’ll see, there is a system within the chaos.

The finicky detail

Before giving up and waiting on the event, there is a bit of aggressive spinning on the spinlock. As is standard with spinlocks, spinning burns CPU on the optimistic premise that it wouldn’t have to do it for long, so it’s worth a go. However, the number of spin iterations is limited. Here is a slight simplification of the algorithm:

- If the scheduler owning the lock is the ambient scheduler, restrict to a single spin.

- Else, give it a thousand tries before sleeping.

- Each spin involves first trying to grab both the lock and (if not yet done) incrementing WaiterCount. If that doesn’t work, just try and increment the WaiterCount.

This being of course the bit where the class knows a thing or two about SQLOS scheduling: If I am currently running, then no other worker on my scheduler can be running. But if another worker on my scheduler currently holds the lock, it can’t possibly wake up and progress towards releasing it unless *I* go to sleep. Mind you, this is already a edge case, because we’d hope that the owner of this kind of lock wouldn’t go to sleep holding it.

To see how scheduling awareness comes into play, I’m going to walk through a scenario involving contention on such a mutex. If some of the scheduling detail makes you frown, you may want to read Scheduler stories: The myth of the waiter list.

A chronicle of contention

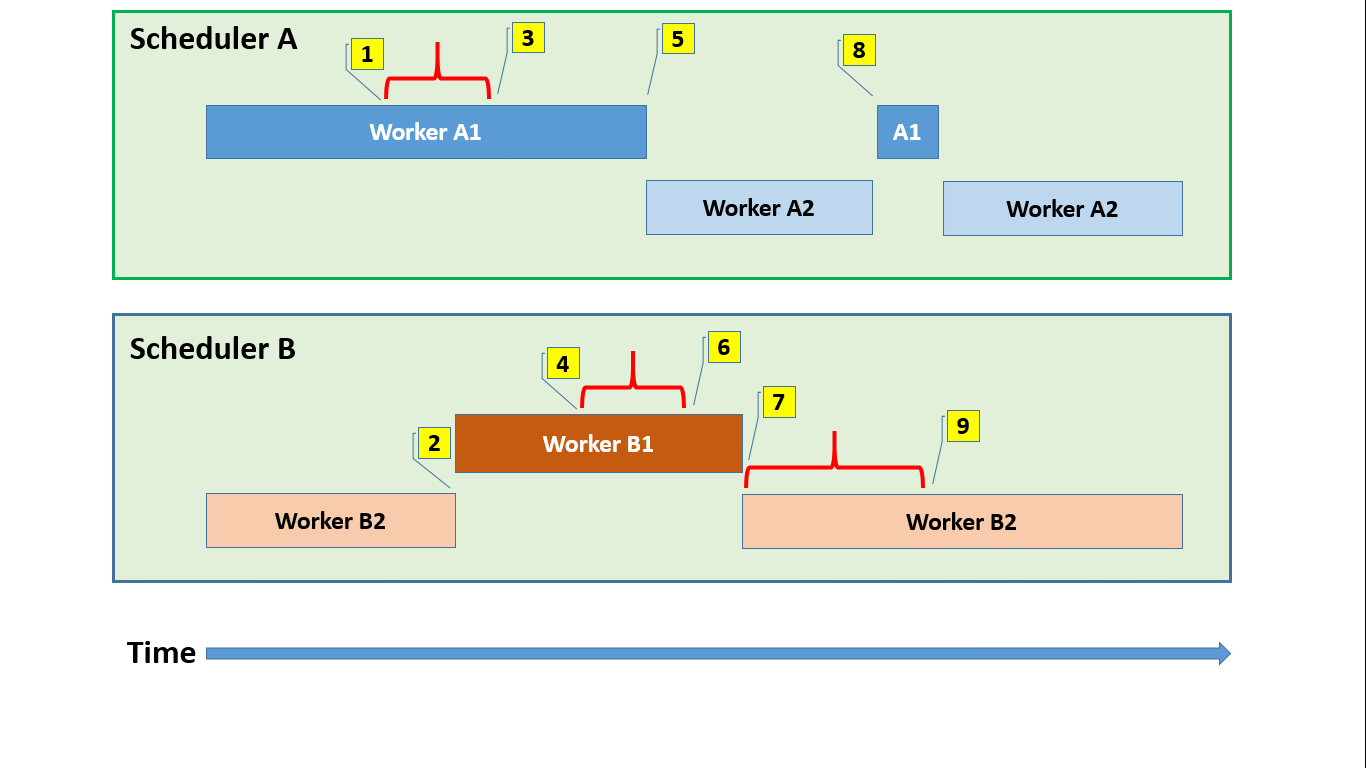

In this toy scenario, we have two schedulers with two active workers each. Three of the four workers will at some point during their execution try and acquire the same mutex, and one of them will try twice. Time flows from left to right, and the numbered callouts are narrated below. A red horizontal bracket represents the period where a worker owns the mutex, which may be a while after the acquisition attempt started.

- A1 wants to acquire the mutex and, finding it uncontended, gets it straight away.

- B2 tries to acquire it, but since it is held by A1, it gives up after a bit of optimistic spinning, going to sleep. This gives B1 a turn on the scheduler.

- A1 releases the mutex, and finding that there is a waiter, signals it. This moves B2 off the mutex’s waiter list and onto scheduler B’s runnable queue, so it will be considered eligible for running at the next scheduler yield point.

- B1 wants the mutex, and since it isn’t taken, grabs it. Even though B2 has been waiting for a while, it wasn’t running, and it’s just tough luck that B1 gets it first.

- A1 wants the mutex again, but now B1 is holding it, so A1 goes to sleep, yielding to A2.

- B1 releases the mutex and signals the waiter A1 – note that B2 isn’t waiting on the resource anymore, but is just in a signal wait.

- B1 reaches the end of its quantum and politely yields the scheduler. B2 is picked as the next worker to run, and upon waking, the first thing it does is to try and grab that mutex. It succeeds.

- A2 reaches a yield point, and now A1 can get scheduled, starting its quantum by trying to acquire the mutex. However, B2 is still holding it, and after some angry spinning, A2 is forced to go to sleep again, yielding to A1.

- B2 releases the mutex and signals the waiting A1, who will hopefully have better luck acquiring it when it wakes up again.

While this may come across as a bit complex, remember that an acquisition attempt (whether immediately successful or not) may also involve spinning on the lock bit. And this spinning manifests as “useful” work which doesn’t show up in spinlock statistics; the only thing that gets exposed is the CMEMTHREAD waiting between the moment a worker gives up and goes to sleep and the moment it is woken up. This may be followed by another bout of unsuccessful and unmeasured spinning.

All in all though, you can see that this unfair acquisition pattern keeps the protected object busy doling out its resource: in this case, an memory object providing blocks of memory. In an alternative universe, the mutex class may well have decided on its next owner at the moment that the previous owner releases it. However, this means that the allocator won’t do useful work until the chosen worker has woken up; in the meantime, the unlucky ones on less busy schedulers may have missed an opportunity to get woken up and do a successful acquire/release cycle. So while the behaviour may look unfair from the viewpoint of the longest waiter, it can turn out better for overall system throughput.

Of course, partitioning memory objects reduced the possibility of even having contention. But the fact remains: while any resources whatsoever are shared, we need to consider how they behave in contended scenarios.

Compare-and-swap trivia

Assuming we want the whole pair, as these memory allocations do, there are four atomic operations performed against the lock member:

- Increment the waiter count: add 0x00010001

- Increment the waiter count and grab the locks: add 0x80018001

- Just grab the locks (after the waiter count was previously incremented): add 0x80008000

- Release the locks and decrement the waiter count: deduct 0x80018001

For the first three, the usual multi-step pattern comes into play:

- Retrieve the current value of the lock member

- Add the desired value to it, or abandon the operation, e.g. if we find the lock bit set and we’re not planning to spin

- Perform the atomic compare-and-swap (lock cmpxchg instruction) to replace the current value with the new one as long as the current value has not changed since the retrieval in step 1

- Repeat if not successful

The release is simpler, since we know that the lock bits are set (we own it!) and there is no conditional logic. Here the operation is simple interlocked arithmetic, but two’s complement messes with your mind a bit: the arithmetic operation is the addition of 0x7ffe7fff. Not a typo: that fourth digit is an “e”!

This all comes down to thinking of the lock bit as a sign bit we need to overflow in order to set to 1. The higher one overflows out of the 32-bit space, but the lower one overflows into the lowest bit of the first count. To demonstrate, we expect 0x80018001 to turn to zero after applying this operation:

8001 8001

+ 7ffe 7fff

---------

(1) 0000 0000

Final thoughts

So you thought we’ve reached the end of scheduling and bit twiddling? This may turn out to be a perfect opportunity to revisit waits, and to start exploring those memory objects themselves.

I’d like to thank Brian Gianforcaro (b | t) for feedback in helping me confirm some observations.